Of Sandhill Cranes and Salmon

Daily doses of awe and wonder may be the prescription we need for chaotic times….

“They're heeeere!!” proclaimed the Rowe Sanctuary Facebook post last Saturday. This announcement stirs the hearts of those who follow the annual sandhill crane migration. Oh, my do we need this good news amid the heartbreak of billionaire bullies and “leaders” with so little compassion! Yet even as we face and respond to the losses and assaults that are accumulating all too rapidly, we are called to the beauty and wonder of this broken-and-still-giving Earth.

If you have seen large scale migrations, please tell us more in the comments. But if you haven’t, or if being reminded of miracles today would feed your soul, I’m happy to share my experience of witnessing this great migration in 2023 by way of an excerpt from my book Earth & Soul:

“Darkness envelopes us as we walk without a word along the trail illuminated only by the faint red light held by our guide. Fresh snow crunches under our feet and sends up waves of cold, colder even than the predawn temperatures, hovering in the teens. A harsh call shatters the silence, so close. High overhead an echoed response and the beating of wings. We have driven for two days and over 1,300 miles from our home in West Virginia to be here, in the middle of Nebraska, to witness the annual migration of sandhill cranes.

“Each spring from March to mid-April, half a million or more cranes leave their winter homes in Texas and New Mexico to fly north. Squeezed into an hourglass flight path, they congregate here on an eighty-mile section of the Platte River to rebuild their strength for the next leg of their journey. Feeding on plants, invertebrates, reptiles, and small rodents from the nearby wet meadows and waste corn from the surrounding farm fields, they will increase their body weight by twenty percent to prepare for travel to their summer homes across Canada or even as far as Alaska and Siberia.

“Cranes have lived on Earth longer than most other birds. Fossils of their relatives dating back ten million years have been discovered. This specific migration path in the center of North America has been used by cranes for many thousands and possibly millions of years. Sandhill cranes and the Platte River forged a relationship that began 10,000 to 12,000 years ago when the river formed after the last ice age. Cranes roost sans trees in the shallowest part of the river. The Platte is a braided river, deepest along the edges with shallows and sandbars in the middle. By putting deeper water between themselves and hungry foxes or coyotes, cranes receive ample warning as predators are forced to splash their way toward a potential dinner.

“Because cranes are legally hunted in 49 states, they are easily frightened by flashes and sudden noises, so we remain in silence as we enter the specially constructed viewing blind where we, like the birds, await dawn. From three to over four feet tall, these gray birds have long, dark, pointed bills and white cheeks punctuated by bright red foreheads. As the sky begins to lighten, they make unique patterns above us, with their necks extended and long legs trailing behind.

“Gradually, they raise their voices until it seems as if every bird is participating in a toccata and fugue in an unnamable key. Perhaps they bugle for the pure joy of making sound. Or maybe to let friends know, “I’m alive! I made it through the night!” The sky brightens, and more birds take flight. Hundreds fly overhead, crisscrossing the sky while hundreds, thousands, more glide in the opposite direction. Back and forth, cranes transect the sky, the sight and sound unlike anything we have known. We are enveloped in a tumult of wings and resounding calls.”1

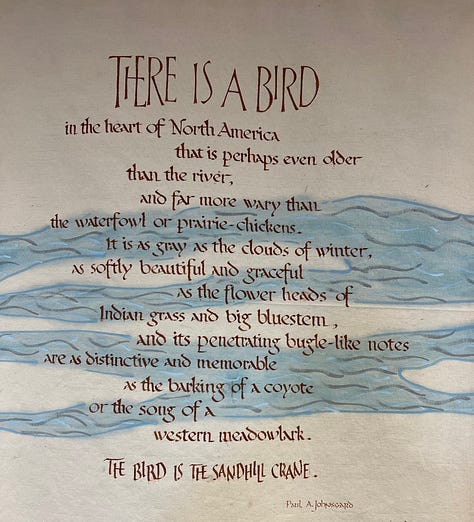

How can we understand the impossible wonder of migrations? As David Abram wrote of the sandhill crane migration: “What is this allurement, this seasonal memory that rises in the muscles, calling one skyward, drawing one back and back again to the place of one’s begetting, to that precise blend of wind and rock and glistening water?”2

Can we picture the journeys undertaken by sea turtles and dragon flies, monarchs and caribou, salmon and sharks? Can we envision the innate capacity of these beings to sense Earth’s language, to know her terrain intimately though countless generations? When we tune in to the endless rhythm of so many lives traveling to and fro, how can we possibly imagine that we have nothing to learn from those whose ancestry dates far beyond that of humans? We are the younger brothers and sisters of these kin, a leaf come lately to the cosmic family tree.

****

The 45-mile Elwha River that flows from Washington’s Olympic National Park to the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the Pacific Ocean was stopped for one hundred years by two dams. Fish ladders were never built to assist the salmon who for countless generations had been braving their way up river to spawn. Restoration of the river began with the removal of the Elwha Dam in 2012. Thanks to the continuous work of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and conservationists, the Glines Canyon Dam was removed in 2014. From here I’ll let Tim McNulty pick up the story in Rewilding Earth:

“Before the last rubble was blasted away from Glines Canyon Dam on Washington’s Elwha River, two bull trout flashed past the dam site and were detected upstream. These intrepid explorers were followed a few days later by the first Chinook salmon. Then coho salmon appeared, then steelhead.

“Once the monumental obstructions of two obsolete and illegal dams were erased from Olympic National Park’s largest watershed, the river’s gates opened. The Elwha’s keystone creatures, Pacific salmon, flooded through to spawn and die in their ancestral waters. With salmon came a pulse of renewal that reverberated through the ecosystem and revitalized the river from headwaters to estuary. Elwha salmon also brought a commodity badly needed in our troubled time: a sense of hope to human communities near and far. The Elwha has shown us a way to reconsider and reverse historic wrongs.”3

There’s something special about a visit to the Elwha, knowing how long her riverness was denied for the sake of electricity for a nearby paper mill. To walk along the remains of the Glines Canyon Dam and see her reclaiming her own path is to catch a glimmer of restorative justice. To walk with our guild from the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe on land where the mouth of the river is weaving her place among her people offers a lesson in kinship and reciprocity.

“If ‘hope is a thing with feathers,’ as poet Emily Dickinson wrote, what could be more hopeful than a sky full of sandhill cranes who each year follow the same path with certainty born of a wisdom we cannot comprehend? What could be more inspiring than a relationship between a river and a species, forged over tens of thousands of years?”4 How can one possibly explain the call of salmon to return time and again to the place of their ancestors?

And still, it’s important to look clearly at these examples: thoughtless or greedy human actions have taken their toll. Ten years after dam removal, the Elwha River and the salmon are still finding their way, reestablishing themselves and the ecosystem to which they belong. The impact of the original dam construction – destruction of extensive ecosystems, elimination of sites sacred to the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, loss of generations of salmon – can never be restored.

Driving through Nebraska to visit the cranes, we passed hundreds of miles of commercial cornfields that depend on irrigation with water from the Platte River or the once vast and rapidly shrinking Ogalala aquifer below. This beautiful braided river is a shadow of its former self. “Roughly 75 percent of wet meadows have disappeared since European settlement, largely due to land-use conversion to cropland and depletion of groundwater supplies. These changes have drastically affected habitat that is critical for numerous species of birds and other wildlife.”5

So much of our own making has cause irreparable harm to this world, too many lives remain at risk, and humans are inflicting needless pain and trauma on each other and all beings. We have too often prized separation over oneness, the wants of the individual over the common good, and the greedy feeding the insatiable ego over the heart’s compassionate wisdom. It’s no wonder that so many experience loneliness as we cut ourselves off from kinship with the living world. We have work to do to reweave our frayed connections to the web of life, to reestablish relationships that bring liveliness and mutual flourishing for all, and to make amends for the damage we have caused Earth.

And still. “Even a wounded world is feeding us. Even a wounded world holds us, giving us moments of wonder and joy. I choose joy over despair. Not because I have my head in the sand, but because joy is what the earth gives me daily and I must return the gift.”6 Ponder what the author is saying here. It’s both/and. We see what’s going on around us. We grieve, lament, speak up, protect. And also. In response to a generous world, it’s my responsibility to receive and return the gift of wonder and joy. Reciprocity.

Right now, over the Platte River, hundreds of thousands of sandhill cranes are feeding, resting and gaining the strength they need to wend their way north as they have done for generations beyond time. Salmon swim in the Elwha River as the nearby land heals. Somewhere very near you, beauty and wonder are awaiting your attention. Will you stop to nourish yourself for the long journey ahead, receiving and returning the gift of joy?

“Bear witness to loss, gaze in awe and wonder, gratefully receive Earth’s gifts, and offer what is yours to give. …. Recognize that you live within a beautiful web of life, primed for mutual flourishing beyond your knowing.”7

Thanks so much to Stacey Remick and Mary O’Hara who shared cloud photos prompted by last week’s post. If you have photos you’re willing to share relative to these posts, reach out via my website.

In-Person Retreat Offerings — I hope you’ll join me for an extended time to connect to Earth and center down.

Discovering the Spiritual Wisdom of Trees: Collaboration and Communication. March 22, 2025, 10am to 4pm, at Well for the Journey, Lutherville-Timonium, MD. Leader: Leah Rampy. Information and registration

Discovering the Spiritual Wisdom of Trees. March 28-30, 2025, Prairiewoods Retreat Center, Hiawatha, IA. Leader: Leah Rampy. Information and registration.

Singing the Trees: Reweaving Connections in Edge Times. April 11-13, 2025, Wellspring Retreat Center, Germantown, MD. Leaders: David and Leah Rampy; Lindsay McLaughlin. Registration and Information

Early Book Sale Alert!

Exciting news! Thanks to our publisher Broadleaf Books, Four Seasons Books will have advanced copies of Discovering the Spiritual Wisdom of Trees available for sale during the American Conservation Film Festival! I will be there March 8 & 9 to personalize your copy. The festival runs from March 6-9 and will feature 28 inspiring films that share stories of hope, resilience, and the individuals making a difference for our planet. Stop by, say hello, and take home your early copy!

Leah Rampy. Earth & Soul: Reconnecting amid Climate Chaos. Chevy Chase, MD: Bold Story Press, 2024, pp. 166-168.

David Abram. “Creaturely Migrations on a Living Planet.” Emergence Magazine. June 8, 2023. https://emergencemagazine.org/essay/creaturely-migrations-breathing-planet/

Tim McNulty. “What the River Teaches: Ten Years After Dam Removal on the Elwha River.” RewildingEarth. July 30, 2024. https://rewilding.org/what-the-river-teaches-ten-years-after-dam-removal-on-the-elwha-river/

Rampy, p. 168.

Robin Wall Kimmerer. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Mildweed Editions, 2013, p. 327.

Rampy, p. 173.

Beautiful, thank you.

My husband and I one year were driving through Iowa at the time of the Monarch Butterfly migrations, and it was sheer tear-evoking joy at what we saw. We pulled over at times or slowed down to try to avoid as much as possible running into any of them. It was like the sky was raining little floating orange-and-black colors. But even just watching the murmurations of starlings or blackbirds attests to the wonders all around us all the time.

I might, with humility, Leah, respond to your observation of cranes following the same path "with certainty born of a wisdom we cannot comprehend," by saying that I'm not so sure we can't comprehend that wisdom--we've only forgotten it in our insane build up and perpetuation of modernity. Is it possible that our very attraction to these things is that still, small voice reminding us of who we really are and from where we come?

I think the wonderful quote from David Abram suggests that forgetting, speaking of a "seasonal memory," and how we are drawn "back and back again to the place of one's begetting, to that precise blend of wind and rock and glistening water." We have forgotten our Origins, cutting us off from that which gives us Life. Robin Wall Kimmerer beautifully reminds us that even with that forgetting, the wounded Earth still feeds and holds us, while reminding us of the need for Reciprocity for that gift. Our ancient "Agreement with the Wild," as Martin Prechtel fashions it, includes that need for Reciprocity in remembering that it is all Holy.

So many lovely ideas, Leah--thank you. I think all of us responders need Substacks just to initiate enough room for conversations on your writings!